Speaking with Contemporary Spanish Urban Artist Germán Bel aka Fasim

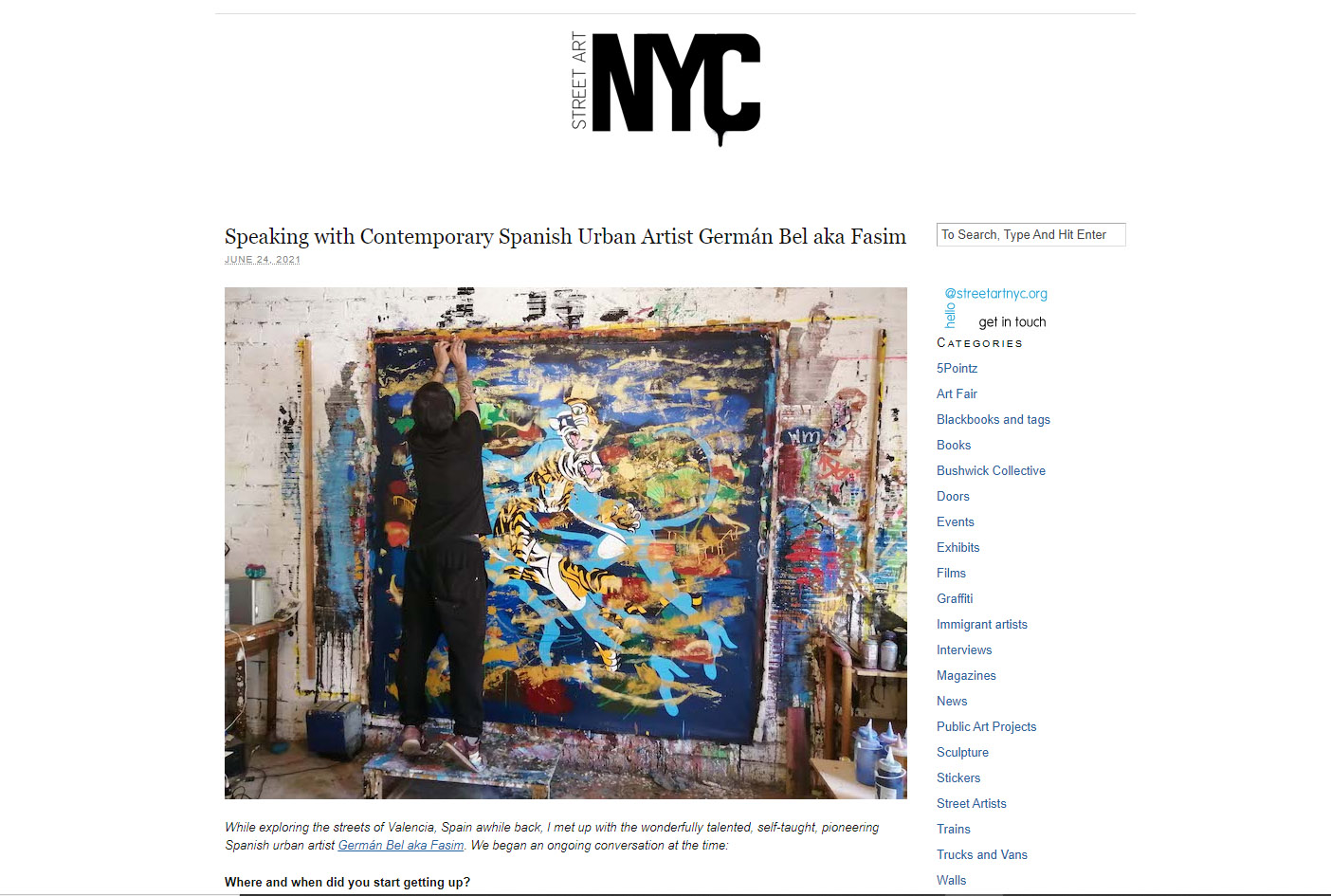

While exploring the streets of Valencia, Spain awhile back, I met up with the wonderfully talented, self-taught, pioneering Spanish urban artist Germán Bel aka Fasim. We began an ongoing conversation at the time:

Where and when did you start getting up?

It was around 1984-85 in the Barcelona neighborhood of La Trinidad. I was 12-13 years old. I started with hair color sprays, colored waxes, paint brushes and any paint sprays that we found at the workers’ construction sites. Spray paint cans were very expensive back then. It was difficult to afford to buy any, although soon we learned to “lift” them without problems!

Who or what first inspired you to get up?

Back in the 80’s, we had very little information about the graffiti movement, and we were lucky that the Style Wars documentary was broadcast on television. It was very instructive; we learned a lot in one night just from watching it. The writer whose style most inspired me was Ricardo Mirando aka Seen. He was undoubtedly the graffiti king!

Have you any favorite surfaces?

All of them have their charm. Painting on large walls is very rewarding, but it is also very exhausting. I prefer painting in open places like public parks. I like the way the art in the public sphere interacts with the citizens and with the urban environment.

My current favorite surface is the canvas; I love its touch and its smell when it’s cut. It can withstand any onslaught! I also like paper. It’s the surface I use most often. It’s lightweight and allows me to generate many works in a short space of time.

What was it like back in the day in Spain?

When we started in the mid 80’s in Barcelona, there were very few tags on the street. But there were other types of writings — mostly alluding to the civil war, Franco’s dictatorship, social injustices, the nuclear threat, the armed group ETA and varied political party propaganda. It was referred to as “pintadas o las pintadas.”

A few years later, murals began to emerge from the punk scene — many related to underground comics and psychedelia. Major European influences included Miss Tic, Blek le Rat and Jef Aerosol.

Can you tell us something about the pioneers of the Barcelona urban art scene?

The pioneers of urban art in Barcelona were called ‘Los Rinos’. They painted giant fried eggs, yogurt containers, paellas, French fries, roasted chickens, dripping spirals – all on train tracks. We found it very funny, and we spent hours sitting on the tracks, smoking and laughing, as we watched them.

Among the many crews in Barcelona were the Kukufruts, an all-girl, all-punk group. Today one of them, Pi Piquer, is a celebrated painter. The Trepax were stencil pioneers and made fascinating stencils of two and three meters. They are wonderfully impressive and, unfortunately, still not documented.

Do you prefer to paint in the street “with permission,” or would you rather do it illegally?

I come from a generation where painting with permission was frowned upon. I painted a wall in a public area in Valencia in 2010 dedicated to war victims. I had grown tired of seeing the horrible deaths and terrible atrocities on television for years. When I arrived with my ladder and paint and started to work, a police car stopped me. But with the help of some neighbors who defended me, I was able to continue. When I finished the wall a few weeks later, I prepared a series of reports that were published in many different cities around the world.

I was proud of what I had accomplished. I had painted a wall with a theme of political and social criticism in the center of Valencia, with no budget and without any permission and with some personal risk. And I was able to promote it around the world. Today the wall is a classic – without the support of any institution.

How did your family feel about what you are doing?

Well, I come from a family that had disintegrated. My life has been somewhat like Huckleberry Finn’s! I ended up living with my maternal grandparents, who lived in a suburb infested with heroin addicts. Its main inhabitants were Andalusian immigrants, with huge social problems.

Although my grandparents liked to see what I painted, they did not perceive it as something positive. They looked favorably on such workers as laborers, receptionists, mechanics… But to be a poet or painter in such an environment was almost a disgrace and a possible death sentence! They believed that one did not earn money with painting — that it was something for troubadours, bohemians or misfits.

They did come to accept it with resignation. Today it is different. Many people come to see my work in exhibitions or on the street. And I am sure that my grandparents, somewhere in the cosmos, would be very happy with my achievements.

What percentage of your time is dedicated to art?

From the time I get up to the time I go to bed. It’s not my job; it’s my life.

What are some of your other interests?

Literature is another great passion. I am a member of INDAGUE (the Spanish Association of Researchers and Disseminators of Graffiti and Urban Art) and I participated in a conference with Fernando Figueroa. More recently, I’ve been preparing some very funny, pictorial literary cut-ups, fusing elements of crime novels, poetry and surreal stories. It’s about the jungle, snake men, talking tigers…. It’s my first foray into literature and I like its subversive, fantastical style. I also love cooking. I love to cook when I have time. It relaxes me and I can disconnect from everything. I love to prepare new dishes.

In New York, there is often a divide between graffiti writers and street artists. Have you any thoughts about that?

I am an artist who has come to painting through tagging. Graffiti helped me to free myself from a very distressing situation of living in a very difficult neighborhood. It was the escape valve. The streets can teach you a vandal-like creative discipline that can move you in the direction of fine art. Tagging is a first contact with artistic creativity.

A few years after I started getting up on the streets, I began to paint. A turning point was my visit to JonOne‘s studio in Paris in the legendary Hôpital éphémère. Jon had original paintings by artists from all over the world including many from New York — like Rammellzee, A-One, Lady Pink, Crash, Futura2000… He showed me books by Basquiat and Miquel Barceló. Walking around his house was like visiting museum. I came to understand the relationship between tagging, graffiti, street art, urban art and fine art.

Nowadays, anyone can buy spray paint, paint a bunch of hearts in an alley, take a picture, upload it to social networks and say he is a street artist. He does this without any threat of arrest — just to be cool, to be trendy. But what he is doing is trivializing the entire movement. He is not a “street artist”. He is just a tool of capitalism.

What about cultural influences?

I am very interested in different cultures, and I have many cultural influences. Art is what survives as a testimony to fallen tyrants, kings, empires, dictatorships, dogmas and religions. What remains is the work of artists, of visionaries and poets, of craftsmen who shaped the ideas of their time. I study art every day, and even when I am studying history or archeology, I always encounter art. Among my many interests is Deir-el Medina, the royal artisan village of the pharaohs in ancient Egypt. These humble artisans who lived in adobe houses crafted many of the incredible works that fill today’s museums.

Today I am more influenced and inspired by my culture — the millenary culture of the Mediterranean — than by all the other modern or contemporary western influences. It is the source of all the elements that make up civilization: architecture, music, painting and sculpture, poetry, philosophy, astronomy and more.

Do you have a formal art education?

I am what others label as “self-taught,” as I study on my own every day — away from the influences of the art establishment. For several months in the early 90’s, I studied painting at the Cucurulla Academy in Barcelona, where we copied natural models and fashioned boring plaster sculptures. My most distinct memory is of a very young, thin model — a heroin addict whose body was filled with bruises. She would fall asleep between poses, and then she would wake up and apologize.

But I didn’t stay in school. I preferred visiting galleries and museums. My favorite gallery was the Joan Gaspar Gallery. It was almost always empty, and there I found original and serial works of great quality by the hands of: Picasso, Braque, Miró, Masson, Clavé, Tàpies, Calder, Viladecans, Mitoraj... For me it was as exciting as entering the Cave of Altamira or Lascaux. Silently facing the works of great, internationally-recognized modern and contemporary creators was my first and my best school. For a young painter, there is no better school than to witness and face these works close-up in museums and galleries. I also read extensively at the time. They were very intense years.

Do you work with a sketch in hand or do you just let it flow?

It depends on what I want to do. In general, I’m always well-organized. When I paint a large-scale mural, I come prepared with a gridded sketch and all of the paint that I’ve chosen carefully with a color chart. When I am going to make illegal pieces on walls, I come prepared to execute them quickly. When I was younger, I used to almost always improvise, but with age I have become more disciplined. Wherever I work, though, I also let the unexpected happen, as that is part of the creative process — even when we think we have lost control.

Are you generally satisfied with your finished work?

With the works I show, I am either half-satisfied or quite satisfied. As a general rule, I don’t show on social media or exhibit something I don’t like. I am quite critical of my painting, and I can repeat the painting process on the same canvas many times until it takes on an unexpected meaning. Life is a mystery, and painting reflects that mystery to us, just as the water reflects the image of Narcissus. While painting, I often become very fond of a piece — falling in love with it or maintaining a deep and ephemeral romance with it during the process.

How has the Covid pandemic affected you and how has it affected your work as an artist?

As you know, it has been a very strong, transformative experience on a planetary level. All our lives have changed radically, and together we are now experiencing a post-traumatic stress, unlike anything we’ve known. I have had to adapt to many changes – some very deep – quickly. I stopped spray painting on the streets in March 2020 at the beginning of the pandemic. I am more concerned now about the harm that sprays can cause the environment. I could do without sprays, but I could not do without painting or drawing. I am horrified by the idea of a world destroyed by selfishness, so I have decided to stop and wait a bit.

I’ve also perceived changes in the direction of my work. I’m now working on themes that a few years ago I would not have imagined. My current series of paintings is tentatively titled “Erased Landscapes.” It has many meanings. It is a metaphor expressing nature’s outrage at us for disregarding our environment, but it also a reference to the mania or obsession to erase all urban graphic signs in big cities, leaving in its wake a trail of strangeerased landscapes. It is also a nod to the idea that a canvas or a painting is a window to another reality, the window within the window.

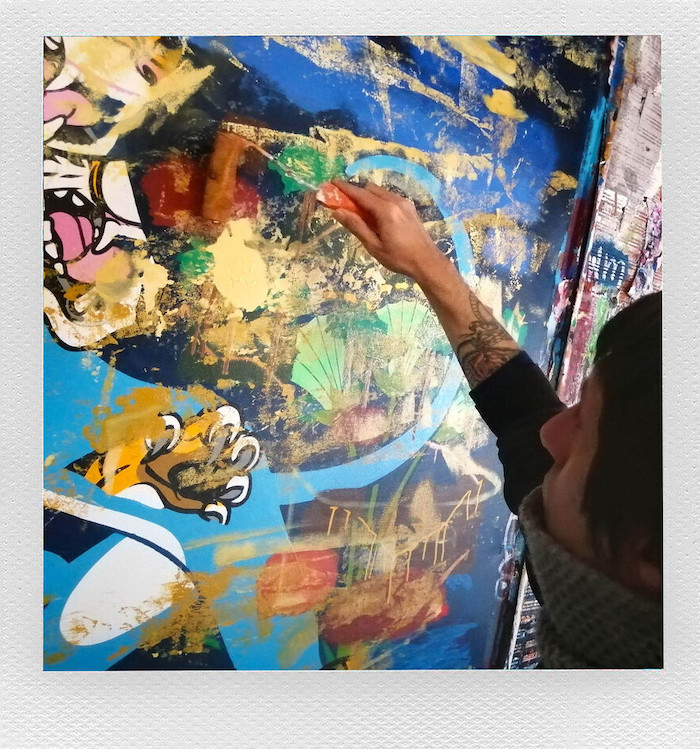

Interview conducted and edited byLois Stavsky

Photo credits: 1-3, 5, & 6 Courtesy of Fasim; 3 Jordi Arques; 4 Lois Stavsky

_________________________________________________________________

Hablando con el artista urbano español contemporáneo Germán Bel alias Fasim

Mientras exploraba las calles de Valencia, España, hace un tiempo, me encontré con el maravilloso artista urbano español, autodidacta y pionero, Germán Bel, alias Fasim. En ese momento iniciamos una conversación:

¿Dónde y cuándo empezaste a levantarte?

Fue alrededor de 1984-85 en el barrio barcelonés de La Trinidad. Tenía 12-13 años. Empecé con sprays de tinte para el pelo, ceras de colores, brochas y cualquier spray de pintura que encontrábamos en las obras de los trabajadores. Los botes de pintura en aerosol eran muy caros por aquel entonces. Era difícil permitirse comprar alguno, ¡aunque pronto aprendimos a «levantarlos» sin problemas!

¿Quién o qué les inspiró por primera vez a levantarse?

En los años 80, teníamos muy poca información sobre el movimiento del grafiti, y tuvimos la suerte de que se emitiera en televisión el documental Style Wars. Fue muy instructivo; aprendimos mucho en una noche sólo con verlo. El escritor cuyo estilo más me inspiró fue Ricardo Mirando, alias Seen. Era, sin duda, el rey del grafiti.

¿Tiene alguna superficie favorita?

Todas tienen su encanto. Pintar en grandes muros es muy gratificante, pero también es muy agotador. Prefiero pintar en lugares abiertos como los parques públicos. Me gusta la forma en que el arte en la esfera pública interactúa con los ciudadanos y con el entorno urbano.

Mi superficie favorita actualmente es el lienzo; me encanta su tacto y su olor cuando se corta. Aguanta cualquier embestida. También me gusta el papel. Es la superficie que más utilizo. Es ligero y me permite generar muchas obras en poco tiempo.

¿Cómo eran los tiempos en España?

Cuando empezamos a mediados de los 80 en Barcelona, había muy pocas etiquetas en la calle. Pero había otro tipo de escritos, sobre todo alusivos a la guerra civil, la dictadura franquista, las injusticias sociales, la amenaza nuclear, el grupo armado ETA y la propaganda de diversos partidos políticos. Se denominaban «pintadas o las pintadas».

Unos años más tarde, empezaron a surgir murales de la escena punk, muchos relacionados con el cómic underground y la psicodelia. Entre las principales influencias europeas estaban Miss Tic, Blek le Rat y Jef Aerosol.

¿Puede hablarnos de los pioneros de la escena del arte urbano en Barcelona?

Los pioneros del arte urbano en Barcelona se llamaban ‘Los Rinos’. Pintaban huevos fritos gigantes, envases de yogur, paellas, patatas fritas, pollos asados, espirales chorreantes… todo sobre las vías del tren. Nos pareció muy divertido, y pasamos horas sentados en las vías, fumando y riendo, mientras los veíamos.

Entre las muchas cuadrillas que había en Barcelona estaban los Kukufruts, un grupo totalmente femenino y punk. Hoy una de ellas, Pi Piquer, es una célebre pintora. Los Trepax fueron pioneros del stencil y realizaron fascinantes plantillas de dos y tres metros. Son maravillosamente impresionantes y, por desgracia, aún no están documentados.

¿Prefiere pintar en la calle «con permiso», o prefiere hacerlo de forma ilegal?

Vengo de una generación en la que pintar con permiso estaba mal visto. En 2010 pinté un muro en una zona pública de Valencia dedicado a las víctimas de la guerra. Me había cansado de ver las horribles muertes y las terribles atrocidades en la televisión durante años. Cuando llegué con mi escalera y mi pintura y empecé a trabajar, un coche de policía me detuvo. Pero con la ayuda de algunos vecinos que me defendieron, pude continuar. Cuando terminé el muro unas semanas después, preparé una serie de reportajes que se publicaron en muchas ciudades del mundo.

Estaba orgulloso de lo que había conseguido. Había pintado un muro con un tema de crítica política y social en el centro de Valencia, sin presupuesto y sin ningún permiso y con cierto riesgo personal. Y pude promocionarlo por todo el mundo. Hoy el muro es un clásico, sin el apoyo de ninguna institución.

¿Qué opina su familia de lo que está haciendo?

Bueno, yo vengo de una familia desintegrada. Mi vida ha sido algo así como la de Huckleberry Finn. Acabé viviendo con mis abuelos maternos, que vivían en un suburbio infestado de heroinómanos. Sus principales habitantes eran inmigrantes andaluces, con enormes problemas sociales.

Aunque a mis abuelos les gustaba ver lo que pintaba, no lo percibían como algo positivo. Veían con buenos ojos a trabajadores como obreros, recepcionistas, mecánicos… ¡Pero ser poeta o pintor en ese ambiente era casi una desgracia y una posible condena a muerte! Creían que con la pintura no se ganaba dinero, que era cosa de trovadores, bohemios o inadaptados.

Llegaron a aceptarlo con resignación. Hoy es diferente. Mucha gente viene a ver mi obra en exposiciones o en la calle. Y estoy seguro de que mis abuelos, en algún lugar del cosmos, estarían muy contentos con mis logros.

¿Qué porcentaje de su tiempo dedica al arte?

Desde que me levanto hasta que me acuesto. No es mi trabajo, es mi vida.

¿Cuáles son sus otros intereses?

La literatura es otra gran pasión. Soy miembro de INDAGUE (la Asociación Española de Investigadores y Divulgadores del Grafiti y el Arte Urbano) y participé en una conferencia con Fernando Figueroa. Más recientemente, he estado preparando unos recortes literarios pictóricos muy divertidos, que fusionan elementos de la novela negra, la poesía y los relatos surrealistas. Se trata de la selva, los hombres serpiente, los tigres parlantes…. Es mi primera incursión en la literatura y me gusta su estilo subversivo y fantástico. También me gusta cocinar. Me encanta cocinar cuando tengo tiempo. Me relaja y puedo desconectar de todo. Me encanta preparar platos nuevos.

En Nueva York, suele haber una división entre los grafiteros y los artistas callejeros. ¿Tiene alguna opinión al respecto?

Soy un artista que ha llegado a la pintura a través del tagging. El grafiti me ayudó a liberarme de una situación muy angustiosa de vivir en un barrio muy difícil. Fue la válvula de escape. La calle puede enseñarte una disciplina creativa vandálica que puede llevarte en la dirección de las bellas artes. El etiquetado es un primer contacto con la creatividad artística.

Unos años después de empezar a salir a la calle, empecé a pintar. Un punto de inflexión fue mi visita al estudio de JonOne en París, en el legendario Hôpital éphémère. Jon tenía cuadros originales de artistas de todo el mundo, incluidos muchos de Nueva York, como Rammellzee, A-One, Lady Pink, Crash, Futura2000… Me mostró libros de Basquiat y Miquel Barceló. Pasear por su casa era como visitar un museo. Llegué a comprender la relación entre el tagging, el grafiti, el arte callejero, el arte urbano y las bellas artes.

Hoy en día, cualquiera puede comprar pintura en aerosol, pintar un puñado de corazones en un callejón, hacer una foto, subirla a las redes sociales y decir que es un artista callejero. Lo hace sin ninguna amenaza de arresto: sólo para ser cool, para estar a la moda. Pero lo que hace es trivializar todo el movimiento. No es un «artista callejero». Sólo es una herramienta del capitalismo.

¿Trabaja con un boceto en la mano o simplemente lo deja fluir?

Depende de lo que quiera hacer. En general, siempre me organizo bien. Cuando pinto un mural a gran escala, vengo preparado con un boceto cuadriculado y toda la pintura que he elegido cuidadosamente con una carta de colores. Cuando voy a hacer piezas ilegales en paredes, voy preparado para ejecutarlas rápidamente. Cuando era más joven, solía improvisar casi siempre, pero con la edad me he vuelto más disciplinado. Sin embargo, donde quiera que trabaje, también dejo que ocurra lo inesperado, ya que eso forma parte del proceso creativo, incluso cuando creemos que hemos perdido el control.

¿Y las influencias culturales?

Me interesan mucho las diferentes culturas, y tengo muchas influencias culturales. El arte es lo que sobrevive como testimonio de tiranos, reyes, imperios, dictaduras, dogmas y religiones caídos. Lo que queda es la obra de artistas, de visionarios y poetas, de artesanos que dieron forma a las ideas de su tiempo. Estudio el arte todos los días, e incluso cuando estudio historia o arqueología, siempre me encuentro con el arte. Entre mis muchos intereses está Deir-el Medina, la aldea real de artesanos de los faraones en el antiguo Egipto. Estos humildes artesanos que vivían en casas de adobe realizaron muchas de las increíbles obras que llenan los museos actuales.

Hoy estoy más influenciado e inspirado por mi cultura -la cultura milenaria del Mediterráneo- que por todas las demás influencias occidentales modernas o contemporáneas. Es la fuente de todos los elementos que conforman la civilización: la arquitectura, la música, la pintura y la escultura, la poesía, la filosofía, la astronomía y mucho más.

¿Tiene una educación artística formal?

Soy lo que otros denominan «autodidacta», ya que estudio por mi cuenta todos los días, lejos de las influencias del establishment artístico. Durante varios meses, a principios de los 90, estudié pintura en la Academia Cucurulla de Barcelona, donde copiábamos modelos naturales y hacíamos aburridas esculturas de yeso. Mi recuerdo más claro es el de una modelo muy joven y delgada, una heroinómana cuyo cuerpo estaba lleno de moratones. Se quedaba dormida entre las poses, y luego se despertaba y se disculpaba.

Pero no me quedé en la escuela. Prefería visitar galerías y museos. Mi galería favorita era la Galería Joan Gaspar. Casi siempre estaba vacía, y allí encontraba obras originales y en serie de gran calidad de la mano de: Picasso, Braque, Miró, Masson,Clavé, Tàpies, Calder, Viladecans, Mitoraj…. Para mí fue tan emocionante como entrar en la Cueva de Altamira o de Lascaux. Enfrentarme en silencio a las obras de grandes creadores modernos y contemporáneos reconocidos internacionalmente fue mi primera y mejor escuela. Para un joven pintor, no hay mejor escuela que presenciar y enfrentarse a estas obras de cerca en museos y galerías. También leí mucho en aquella época. Fueron años muy intensos.

¿Está generalmente satisfecho con su obra terminada?

Con las obras que expongo, estoy medio satisfecho o bastante satisfecho. Por regla general, no muestro en las redes sociales ni expongo algo que no me gusta. Soy bastante crítico con mi pintura, y puedo repetir el proceso pictórico en el mismo lienzo muchas veces hasta que adquiere un significado inesperado. La vida es un misterio, y la pintura nos refleja ese misterio, igual que el agua refleja la imagen de Narciso. Mientras pinto, a menudo me encariño con una obra, enamorándome de ella o manteniendo un profundo y efímero romance con ella durante el proceso.

¿Cómo le ha afectado la pandemia de Covid y cómo ha afectado a su trabajo como artista?

Como sabes, ha sido una experiencia muy fuerte y transformadora a nivel planetario. Todas nuestras vidas han cambiado radicalmente, y ahora estamos experimentando un estrés postraumático como nunca antes habíamos conocido. He tenido que adaptarme rápidamente a muchos cambios, algunos muy profundos. Dejé de pintar en las calles en marzo de 2020, al comienzo de la pandemia. Ahora me preocupa más el daño que los aerosoles pueden causar al medio ambiente. Podría prescindir de los sprays, pero no podría prescindir de pintar o dibujar. Me horroriza la idea de un mundo destruido por el egoísmo, así que he decidido parar y esperar un poco.

También he percibido cambios en la dirección de mi obra. Ahora estoy trabajando en temas que hace unos años no habría imaginado. Mi actual serie de cuadros se titula provisionalmente «Paisajes borrados». Tiene muchos significados. Es una metáfora que expresa la indignación de la naturaleza hacia nosotros por despreciar nuestro entorno, pero también es una referencia a la manía u obsesión por borrar todos los signos gráficos urbanos en las grandes ciudades, dejando a su paso un rastro de paisajes extrañamente borrados. También es un guiño a la idea de que un lienzo o un cuadro es una ventana a otra realidad, la ventana dentro de la ventana.

Entrevista realizada y editada por Lois Stavsky

Créditos de las fotos: 1-3, 5 y 6 Cortesía deFasim; 3 Jordi Arques; 4 Lois Stavsky